Please note: All views expressed in this piece are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official position of SME Water… not that SME Water has an official position on football.

Football. As the wildly overused phrase goes, is ‘a funny old game’. With many Liverpool fans still trying to shake off the post-weekend malaise, it falls to me to add some more words to the growing number of column inches that have been written about the events surrounding what was a bang-average Champions League final. Not the travails of fans at the match in Paris though, nor details of the sluggish game itself. This blog will present a look at the game’s funny old impact on people’s behaviour and water consumption habits in Liverpool and Manchester.

Sporadic large-scale changes in demand can cause notable issues for utilities companies in the UK. You might be familiar with the fact that the British National Grid experiences a power surge during half-time of the World Cup final as legions of football fans get up en masse to make a brew, but what happens to water consumption during large sporting events, such as the weekend’s Champions League final? Surely these same people have to fill their kettles, to say nothing of the half-time sprint to the loo. We thought it would be interesting to investigate the impact on demand and to what extent your region’s leading football team being in the final influenced water consumption patterns.

As many will be aware, this year the otherwise imperious Manchester City botched their semi-final against Real Madrid, setting Liverpool and Madrid up for what was hoped would be a replay of the 1981 final in Paris (with Liverpool winning 1-0), rather than the 2018 final – the last time Liverpool met Madrid to contest the cup. Reds fans will no doubt remember that as the match in which Spanish centre-back Sergio Ramos intentionally brought the scintillating Mo Salah to ground, resulting in the Egyptian King’s injury and subsequent substitution.

Enough football trivia though. With it having been stipulated that, for many, Ramos will forever be remembered as a pantomime villain of yesteryear, a cad, a bounder, a… (there are remarkably few safe-for-work descriptions if I’m honest), let’s move on to regional water consumption.

Is it possible to detect a jump in water usage at the highly predictable times when large television audiences nip to the loo in both regions?

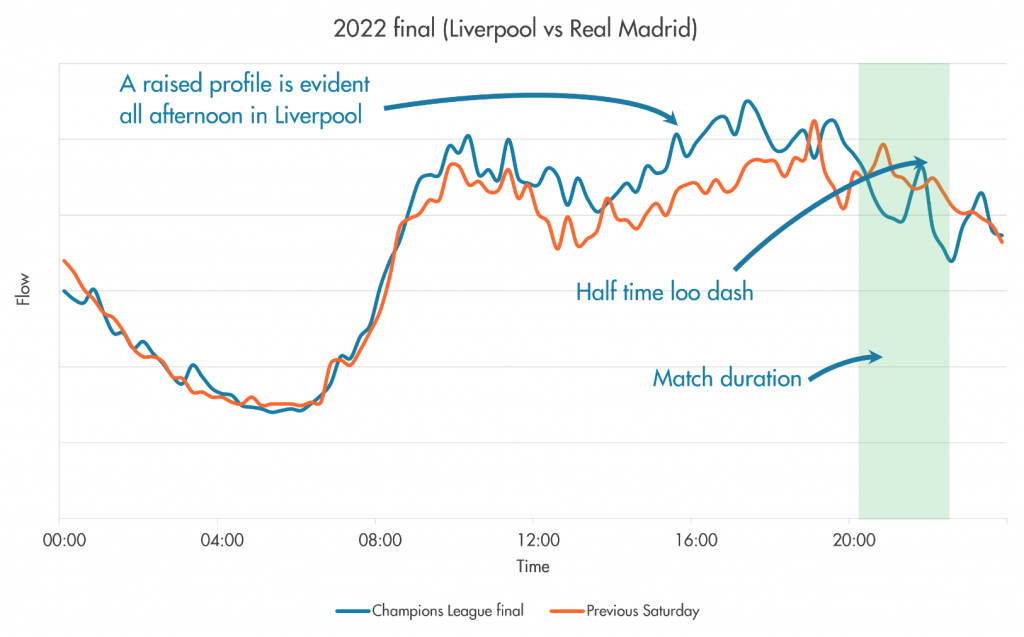

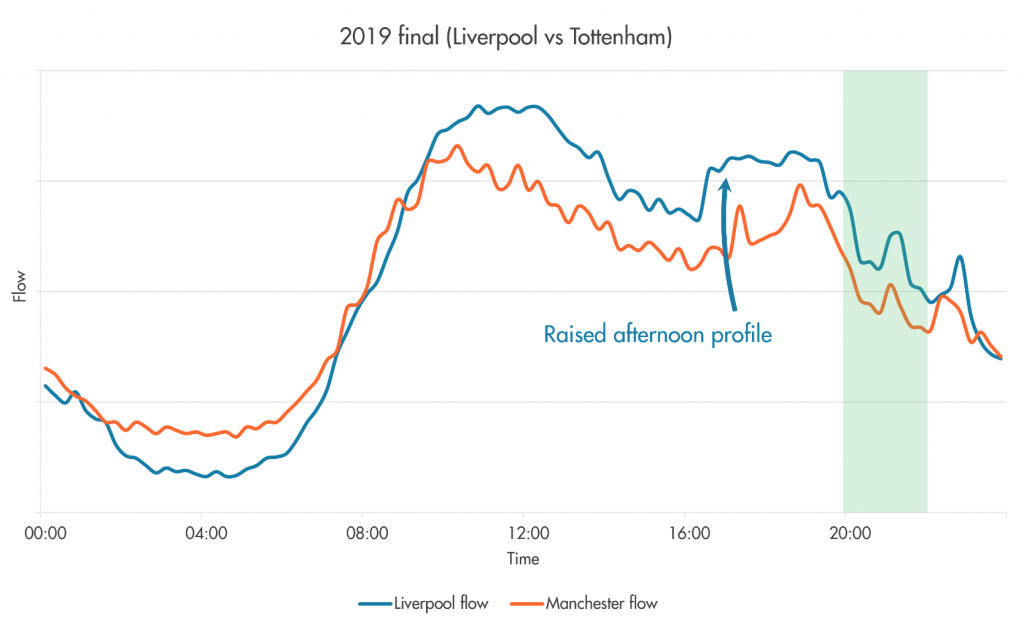

Below is a graph showing a central Liverpool area’s water consumption on the day of the match as well as a comparison to the same day in the previous week. In addition to the expected half time loo dash, we can see that on the Saturday of the final, demand was raised significantly all afternoon in the city of Liverpool as fans travelled to be a part of the pre-match atmosphere. The last time this afternoon long peak in demand was evident was back in 2019. In contrast, we also see that during the match water consumption actually dipped below the previous week’s.